The past 25 years seen substantial reform for both the American and Canadian social safety nets. In both countries, programs for low-income families with children have evolved significantly, more than in almost any other policy area.

In their new paper, “How do the U.S and Canadian social safety nets compare for women and children” Martin Prosperity Institute fellow Mark Stabile and co-author and Berkeley professor Hilary Hoynes examine the evolution of these policies across both countries, while measuring how each has fared in achieving their goals.

The systems share similarities, and yet there are notable differences between programs, reflecting each nation’s distinctly different goals. The U.S. system, built on work requirements, leads to poverty improvements that reflect relatively more gains in market wages while the Canadian system, mainly without work requirements and more universal, leads to poverty improvements more through the benefit system. Additionally, Canada offers higher levels of assistance compared to the U.S. leading to lower poverty rates.

In 1990, most low-income families with children, the main target of these programs in both countries, primarily depended on cash welfare benefits. Today, the U.S. Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and the Canadian National Child Benefit (NCB), and its successor, the Canadian Child Benefit, have mostly replaced such benefits. They now make up the backbone of the social safety net for low income families with children in both countries. They also represent a major change in the structure of the social safety net for single mothers in both countries, reflecting a move away from relying primarily on traditional cash-based welfare benefits. Instead, both programs encourage labor force participation, either through work requirements (EITC) or lessening the welfare cliff (NCB).

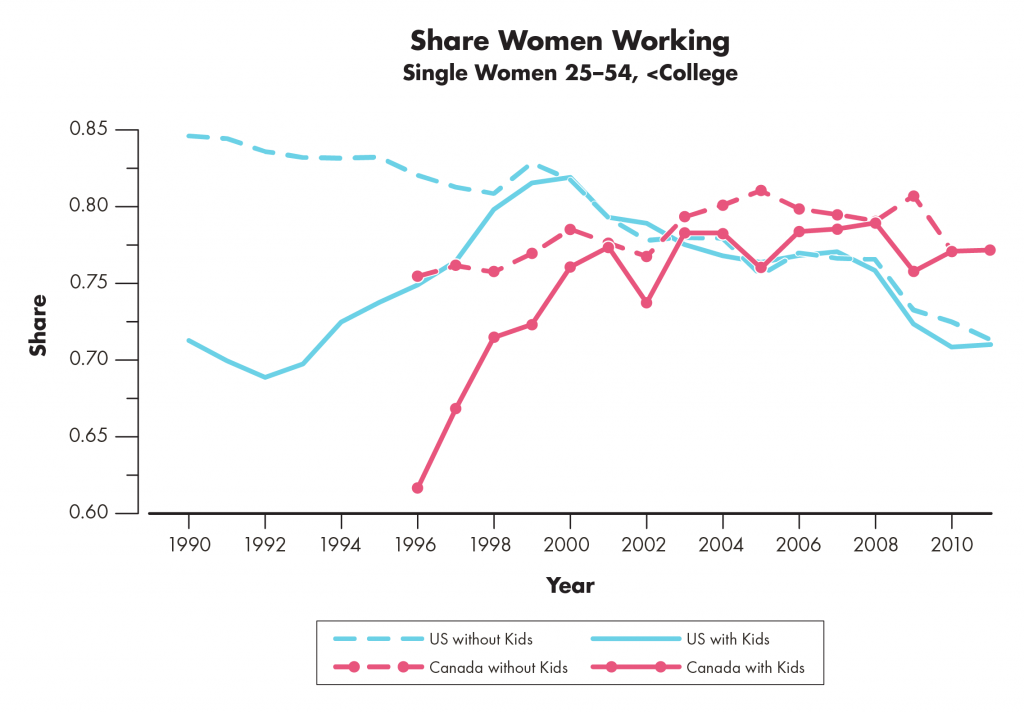

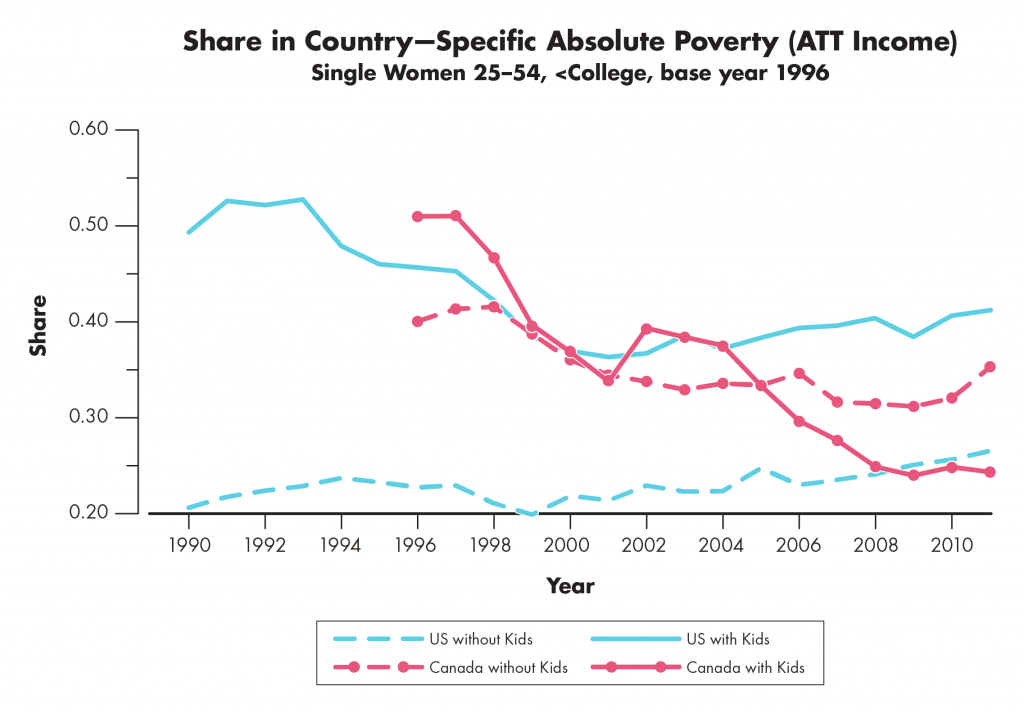

Overall, both programs have had positive effects on labor force attachment and poverty. Employment for single mothers without college degrees has increased, catching up to employment for childless women. While employment for single women (with and without children) declined in the U.S. after 2000, this decline stems from differences in the U.S. labour market, rather than changes to the social safety net. After accounting for a weaker post-2000 American labour market, poverty declines across the two countries are quite similar.

Over this period, both programs are associated with a reduction in poverty rates among single women with children, with the overall incidence of poverty lower in Canada, thanks to a more generous system and stronger cash welfare program. While the effects of these policy changes on poverty for single mothers are similar across the two countries, they also reflect different policy choices. It appears that market income plays a larger role in the U.S. – consistent with the stronger employment incentives inherent in the EITC – while benefit income may play a relatively larger role in Canada. Finally, the weakness of the out-of-work safety net in the U.S. suggests the county would experience higher rates of deep poverty compared to Canada, particularly for those without work.

While these programs have increased in generosity over the past 25 years, a good deal of poverty in both countries remains concentrated among female headed families with children. More could be done to understand the broader impacts of the social safety net on the distribution of income and inequality in the two countries.

Download this Insight (PDF)